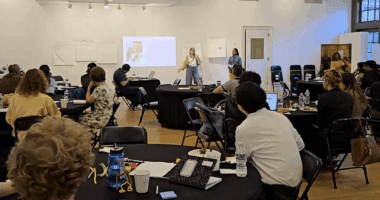

The Teaching Artist Project (TAP) has given me hope. Hope is an abstract noun. We can’t see it, but we can feel the abstraction. This feeling was awakened when ruminating on my final project for my fieldwork concentration: Arts Education Administration. I chose the Arts Education Administration fieldwork because I wanted to gain formal knowledge on project development, grant-writing, and how I could use my teaching artistry to enhance my administrative skills, and reciprocally.

For my fieldwork, I was asked to form a group for thought partners. My other three partners are developing a project, too. While our projects are different in terms of age group and artistry, I have learned from their experiences in schools, as a teaching artist, and as a grant-writer. Much of my knowledge about grant-writing has been from informal training. In other words, I have taught myself. Sometimes, I get self-conscious. My thought partners have revealed their vulnerabilities, too, in this process. While we are not in-person present, I still feel connection and community over Zoom.

Last week my thought partners and I researched in silence for some time, but I didn’t feel lonely. The silence would break when one of us needed to talk or had a question. In some ways I found the silence comforting. Even though we were muted, I had zoom open on the upper left corner of my screen. I saw scrunched eyebrows, arm stretches, and light casting every time a new page opened. This collaborative experience made me think about the space between sight and the sound of words.

Seeing comes before words. There is another sense in which seeing comes before words. Seeing forms our place in the surrounding world; we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by the world. The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. Each morning we see the sun rise. We know that the earth is turning to the sun. Still, the knowledge and the reason, never quite fits sight. The surrealist painter, Magritte, commented on this always-present gap between words and seeing in a painting called The Key of Dreams.

When thinking of creative elements, the space between is my force. I live in the space between. As a multilingual human, educator, and poet, I see the space between sight and objects. The space between is the relationship. This relationship embodies a synthesis of mediums. The conception of words and images relates to awareness. The realization of awareness is the ability to see and the recognition that we, too, can be seen. These ways of seeing construct a sense of credibility that we, humans, are part of the visible world. Language is an attempt to articulate how one sees and unravels the world. And so, discourse has a sense of harmonious exertion.

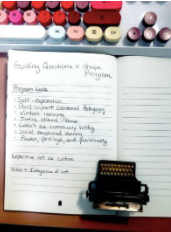

When journaling about the space between in relation to discourse, I thought of my craft: poetry and creative writing. I thought of my values and beliefs in relation to my teaching practice. I thought about language. Language is possibility. Like poets, multilinguals, too, have the ability to see openly and deeply. There is an art to seeing. Poets and multilinguals have this superpower that still is not widely accepted. As a multilingual first-generation Assyrian-Syriac-Iraqi American woman and poet, the lack of acceptance is a familiar rhythm in my narrative. After reflecting with my fieldwork facilitator, Katie Rainey, I realized my core creative force for my fieldwork project is to create a program that sees the nature of poetry in language and the value of multilinguals. Furthermore, my guiding question for my project is: How do I negotiate my power to empower my participants?