To marry “art” and “activism” is a high order task, which came up came up during the second session of the Inclusive and Collaborative Art fieldwork session. We had the following definitions for the two words: “art” as the divine language and “activism” as the action to achieve a political or social result. The two concepts are hardly mutually exclusive. By grade school, we would all recognize Rosie the Riveter in our social studies textbooks as the propaganda and recruitment icon of women laborers during World War II.

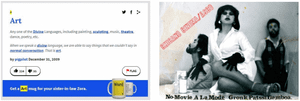

The concept brings about a longer slew of self-inquiries: how could we as teaching artists utilize our art forms to elevate our organizing and activism? How can we use our unique skills to communicate in a way that everyday speech cannot? The art group Asco is an example of “collaborative…[both] aesthetic and agitational” in challenging art spaces and mass media depictions of Latinos and Chicanos in the 1970s. They would do this through “No Movies,” in which they would create scenes as if they were stills from a Chicano-produced film and circulated through the postal system both nationally and internationally (Williams Magazine).

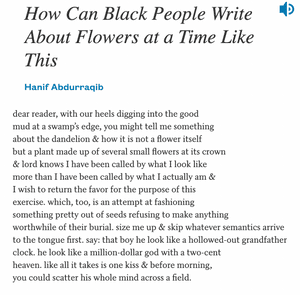

Hanif Adurraqib’s poem “How Can Black People Be Writing About Flowers at a Time Like This,” written shortly after the 2016 election, similarly explores this idea. At a reading, Abdurraqib overhears a white woman asking that titular question, simultaneously framing Black poetics in a particular lens and questioning the possibility of writing anything other than Blackness and racism. This is a familiar pigeonholing and essentializing of POC discussions on the topics of race, trauma, and violence, as it is expected by a white readership. This also puts the onus on POCs on how to safely explore topics other than trauma while still centering and honoring our identities and experiences. Amplifying Black joy or pleasure does not come at the expense of erasing the history of pain. Black joy is a possibility and a kind of resilience when the culture we live in capitalizes on the spectacle of suffering and hurt. Cathy Park Hong talks about this consciousness while working on her book of essays Minor Feelings:

For me, [this] crystallized the notion that we as humans have this irresistible desire to see violence because of the adrenaline sensation of horror it gives us, without any of the consequences… because as someone who writes in American culture, my talent is measured by how much I hurt on the page… Was it to satiate the appetite of a broader American audience, or a white audience—to allow them to take a ride in my reality before arriving at some kind of self-affirmation?

In the fieldwork discussion with my fellow teaching artist trainees, we talked about art and movements born as a response to injustice, like Pride Parade originating from the 1969 Stonewall Riots as well as visual artist Adrian Brandon’s Stolen Series, in which he uses time as a medium to draw his subjects, all of whom were stolen by police violence and white supremacy (“1 year of life = 1 minute of color. Tamir Rice was 12 when he was murdered, so I colored his portrait for 12 minutes”). We must not forget that as the coronavirus swept through New York City during the wake of the George Floyd protests in June of 2020, folx marched in the streets of Williamsburg with cries of “Fire, Fire, Gentrifier!” That became one of the rallying anthems of marginalized groups pushed out by housing developments and luxury rentals. The artist’s duty is manifold: we are tasked in archiving history in a way that is more reliable than the narratives created by systems oppressing us as well as organizing our communities to generate social impact.

As we are rounding out the end of the Teaching Artist Project in the Inclusive and Collaborative Art Fieldwork, we are focusing on a collective project answering to the prompt of “joy as an act of resistance” in the framework of mental health and the pandemic: To wit:

What does joy look like to you?

How do you access joy?

What is joy in other languages that you speak?

More important for me through TAP is generating these kinds of burning questions. Questions to revisit over and over again in our artistic careers, no less. I am also very honored in connecting with insightful, wildly talented artists and amazing facilitators who share this divine language of art. Not only is knowing how to speak art important but also the very act of artivism is ensuring accessibility to quality arts education. I think of my own educational practice and social services work as a pathway to advocate for young people— or as E.D. Hirsh concisely says, “only a well-rounded, knowledge-specific curriculum can impart needed knowledge to all children and overcome inequality of opportunity.”